Reflections on University

Time to read: 39 min read

If you haven't already, check out my reflections on working in co-op and sample co-op trajectories in the fields of tech and business.

Having now completed both my university degrees, I am now more than qualified to answer some age-old questions about post-secondary education. Before doing so, I’d like to take some time to reflect on my experiences with school to provide some backdrop for the discussion.

# My Experience with School Pre-University

Growing up in an Asian household, education was an important aspect of my life. From a young age I was led to believe that education, especially formal education, is a necessary step for improving one’s station in life. Education for me has always been gospel; as with almost all religions, the more devoted the disciple, the more effort one has to make to justify their worth and find meaning.

From waking up at 6AM daily to memorize English vocabulary in grade 2 to bussing over 3 hours daily to attend a public IB high school, it’s safe to say I have been a zealous believer in the cult of education. To be fair, while my parents were supportive of my educational endeavors, they never forced it upon me; I genuinely enjoy learning and the competitive nature of schools fit well with my personality. As a result of my devotion and my family’s support, I managed to consistently perform well in school, both in terms of grades, such as graduating high school with a comfortable 4.0 GPA, as well as extracurriculars, such as volunteering for various organizations, competing in track and field, and attending provincial-level debate competitions.

When applying for universities, my mother assured me that she would 砸锅卖铁 (an idiom in Mandarin which means to literally “smash the cooking pans to sell the scrap metal”) to ensure that I would be able to attend the school and pursue the study in my field of choice. While the idiom was (probably) a hyperbole, it terrified me to have to burden my mother with the expenses and costs of my education so I opted to apply only to schools in Canada, so that I can pay for most, if not all the expenses through working and student loans.

My two favourite subjects in high school were history and physics; for the longest time, I seriously considered professionally pursuing those fields, as well as derivative fields such as philosophy and math. After doing much soul-searching and googling the career prospects of the different fields, I opted to pursue engineering, as both my parents are engineers and engineering contained a great deal of physics and math.

My top two choices were Engineering Science at University of Toronto, because it’s the most exclusive program in Canada, and Systems Design Engineering at University of Waterloo, because it’s the engineering program with the highest average salary after graduation. I also applied for back-up programs, the two main ones being the Ivey/ Engineering dual degree program at Western University and the Computer Science/ Business Administration dual degree program at University of Waterloo and Wilfrid Laurier University. I ended up being accepted into all the programs except my first choice, which was Engineering Science. I spent weeks debating which engineering program from which university I should take. In the end, almost as a spur-of-the-moment decision, I chose to forgo engineering and to instead take the CS and BBA program from Waterloo and Laurier. I liked how I can learn both hard and soft skills, and the $5000 per year scholarship definitely helped sway my decision as well.

# Failure

University was the first time I lived alone away from home for a prolonged period of time outside of summer camp. Adjusting to university life was difficult for me, while I was by no means being sheltered back at home, the sudden influx of freedom and optionality threw a wrench into my usually scheduled days.

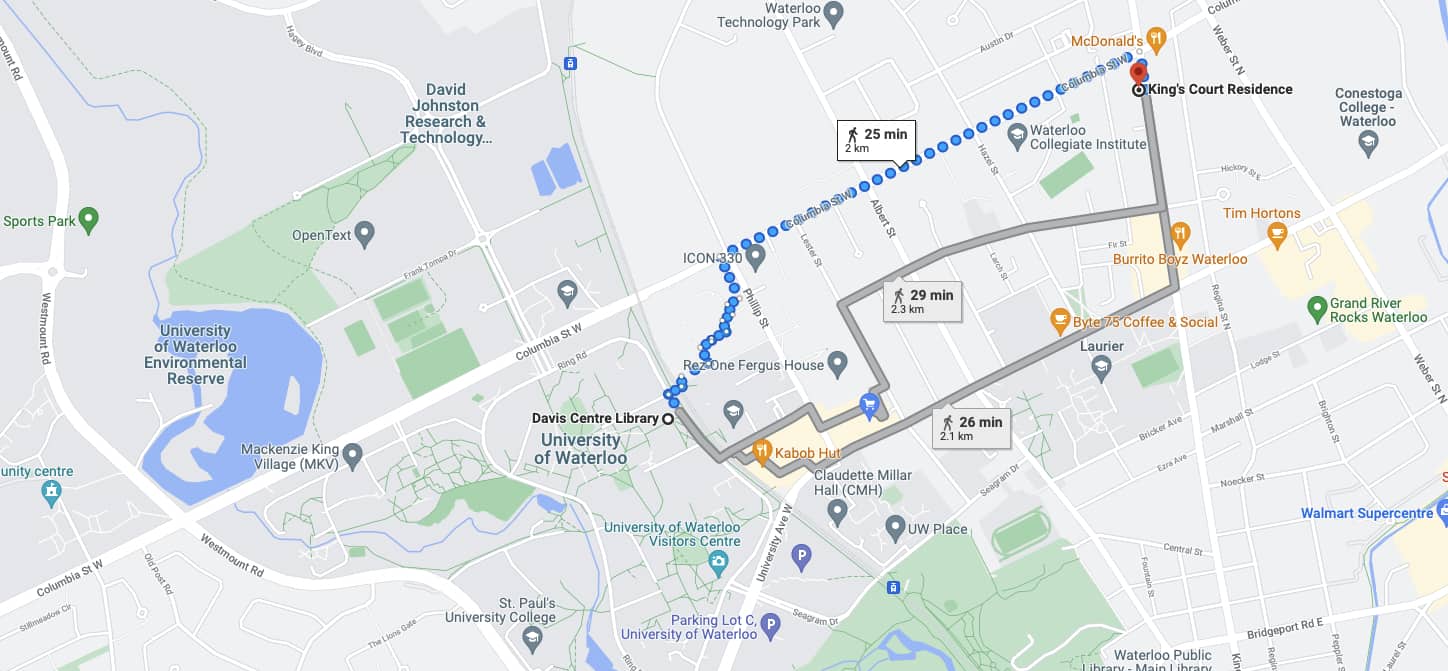

I had also failed to understand the implications of which university I applied to; I had applied to the double degree through Laurier due to the higher scholarship amount, but it also meant I had to live in the Laurier dorm. I picked an apartment-style dorm to have my own room but had to live in King’s Court, which was over half a kilometer away from the Laurier campus and over two kilometers away from the Waterloo campus, where most of my friends lived. Living so far from academia definitely affected my willingness and ability to both study and to socialize, this was definitely a gross oversight on my part.

Map of King's Court relative to the campuses

Map of King's Court relative to the campuses

Furthermore, my Laurier roommates had different priorities (namely partying and having a good time); two of my roommates partied so hard they dropped out of school after first year. Needless to say, such an environment was not conducive to learning and I felt isolated because I didn’t (and couldn’t afford the time to) share the same interests and hobbies as the people around me.

I also struggled greatly with academics. In high school I had excelled at all my courses with minimal effort and thus was overly-confident in my abilities as a learner. In university, however, I quickly found out just how much of a joke the Ontario secondary education system really is. I was fortunate enough to attend the IB program, but even with the more rigorous curriculum, I found myself lagging behind my international compatriots in terms of both knowledge as well as learning and studying skills. Furthermore, I had never written a line of code before university, and the first year CS courses at Waterloo, with its variable difficulty targeting a low-70s course average, were designed to weed out the weak (which unfortunately included me at the time). I was thus indirectly competing with people who had years, sometimes over a decade, of coding experience.

I had also failed to do research on course selection and ended up in a section with a prof, which to this day, has the only RateMyProf profile I’ve come across with only one star reviews. Needless to say, I bombed my CS course, and bombed hard, barely scraping by with a grade in the 60s. This greatly shattered my self-esteem and self-perception and I seriously considered dropping CS to do just the Math/BBA dual degree, as I was still following along in my math courses. I felt like the frog in the bottom of the well, finally realizing their insignificance and mediocrity in the (slightly) broader world.

My first foray into university was a disaster. Despite thinking that university would be about fun and parties, I ended up spending most of my time in the library and ended the semester with fewer friends than I started out school with. Even with spending all of my time in the library, I failed at my studies so badly that I lost my scholarship after the first year. One of the few upsides of failing so completely is that I was able to take greater risks without fearing for further downside; in other words, I could not have fucked up more than I already did. This was extremely liberating.

I remember being very envious of people in my program who appeared to not only be able to maintain a healthy social life but also excel at their studies with seemingly minimal effort. It became clear that I was not yet at their level and that for me to excel, I had to make some harsh decisions on how to best allocate my time and energy. Like an ascetic from the days of yore, I isolated myself from my surroundings, especially from activities and relationships which I felt no longer aligned with my goals, such as foregoing parties and drinking, and going so far as to break up with my then-girlfriend.

# Growth

Even though I consider myself introverted, the period after my first semester was rough. Not having any social life is brutal; it felt as if all the dopamine in my body was drained down to the very last drop. Through the powers of meditation, I was able to conquer the dread of being a loser. Other than meditation, my only other reprise from the painful process of growth is consistent exercise; after a day of studying in the library, I’d strap on my joggers and run to the fields behind the university. The fields are usually empty of people after midnight and are completely unlit. After adjusting my vision, I’d be alone with the sounds of insects and the whispering of the leaves. On clear nights, running under the moon and the stars filled me with a great sense of purpose.

I had to accept and face all of my shortcomings and failures; I had to check my overinflated ego and acknowledge that, compared to many of my peers, I was an idiot. Due to the fact that I had never bothered to learn study techniques in high school, my learning was highly inefficient. My brain was not accustomed to ingesting so much information and struggled with performing rigorous logical analysis for prolonged periods of time. I’d constantly find myself rereading the same paragraphs or the same equations over and over again and still not fully grasping the content. With perseverance and raw drive, my brain slowly adapted and the activity of learning not only became easier, but actually enjoyable. The miraculous malleability of the human brain amazes me even today.

Learning for me became a virtuous cycle: the more I learned, the easier learning became and the easier learning became, the more I learned. Studying was no longer about surviving my program, it became enjoyable. Furthermore, I found myself attracting and being increasingly surrounded by people with similar goals and aspirations. My newfound network inspired me to work even harder and learn even more.

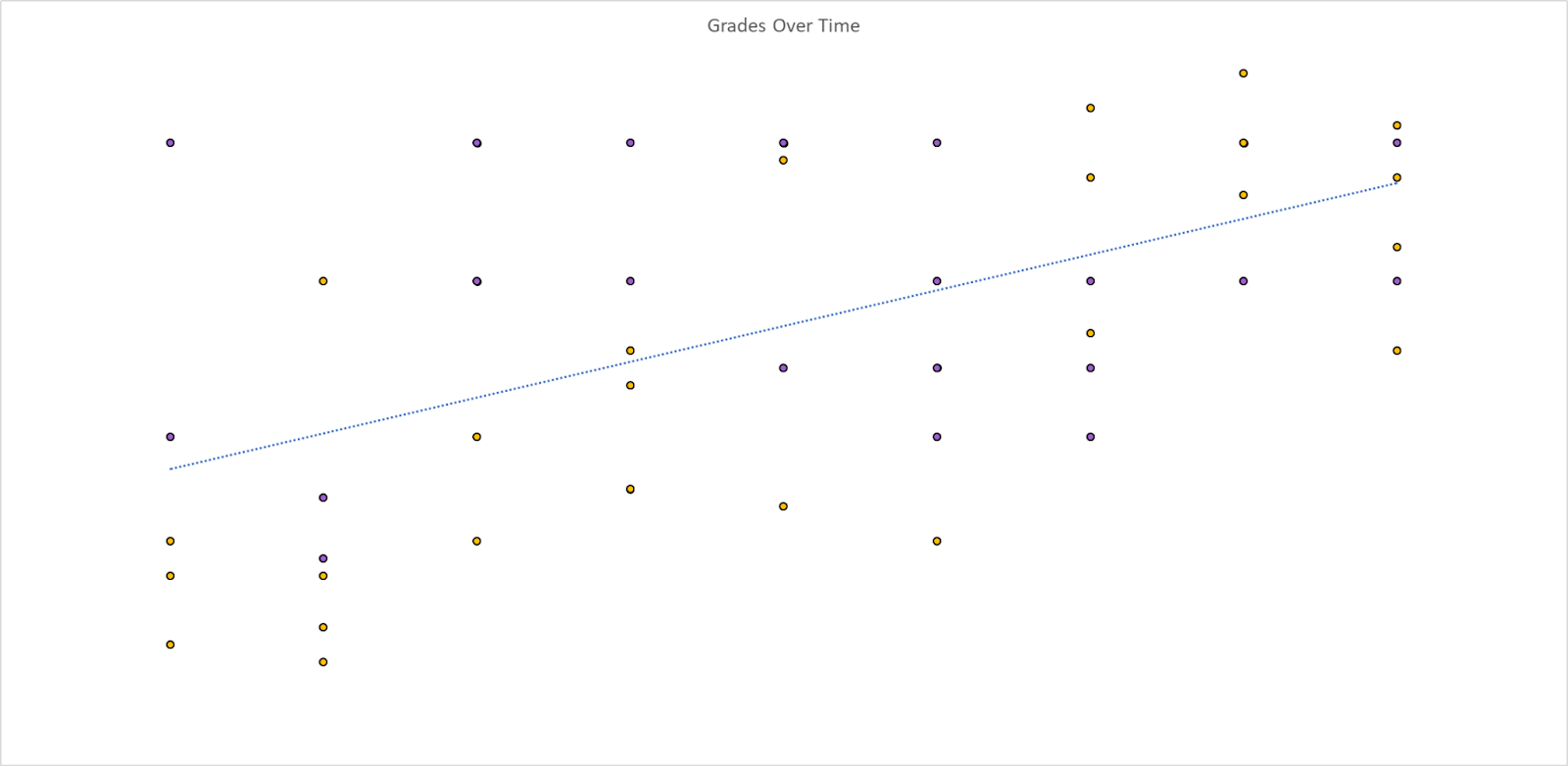

Grades over time; yellow and purple points correspond to UW and WLU courses, respectively. WLU grades converted by averaging range; certain data points are overlapped with one another

Grades over time; yellow and purple points correspond to UW and WLU courses, respectively. WLU grades converted by averaging range; certain data points are overlapped with one another

# Courses

Rating Every Course I've Taken in University

It’s no secret that the most value-add and interesting courses are only available in upper years; this is especially the case with the double degree program, where my course schedule was filled with mandatory courses for the first three years of university. Some of these mandatory courses were helpful, especially for someone like me, who had minimal exposure to business and computer science prior to university. This was the case for many of the first year general introduction courses both at Laurier and Waterloo. The general introductory business course (BU 111) and econ courses (ECON 120 and 140) from Laurier, and the introductory math (MATH 135) and coding courses (CS 135 and 136) were particularly valuable for my learning and academic growth.

Most of the mandatory courses, however, were a waste of time. I found this to be especially the case for many of my second-year Laurier courses where the goal was to memorize and regurgitate jargon. I enjoyed most of the mandatory Waterloo CS courses but found many of the mandatory math courses to be overly theoretical.

The upper-year electives at both Laurier and Waterloo were amazing. On the Laurier side there were many capacity-limited courses where students had to apply and interview for. Those courses tend to cater towards people interested in consulting and finance. For students interested in consulting, notable courses include Laurier JDCC, the competitive case competition team where students participate in case competitions representing Laurier, and Lazaridis Management Consulting Practicum, where students consult pro-bono for different non-profit organizations. For students interested in finance, notable courses include Laurier Student Investment Fund (LSIF) and Laurier Start-Up Fund (LSUF), where students perform due diligence on public and venture companies, respectively. Alumni from Big Three consulting firms as well as from numerous investment banks and investment firms are heavily involved in helping and mentoring students within said courses, making for an excellent networking opportunity as well. There were also many experimental courses started by professors as passion projects; my favourite Laurier course, covering market microstructure (BU 493U), was one such course.

On the Waterloo side, there weren’t many exclusive courses where one receives extensive one-on-one time with professors and mentors, but there were many interesting courses from various fields. Highlights for me included Applied Cryptography (CO 487) where there were many interesting stories about hacks and breaches and Data-Intensive Distributed Computing (CS 451) where the assignments were incredibly useful. As with many of the interesting Laurier courses, many of the upper-year Waterloo courses contained large hands-on components, whether it’s building large projects or conducting research projects.

I found that generally Laurier lectures were more enjoyable than Waterloo lectures. This is due to Waterloo lectures being highly technical and rigorous while the Laurier lectures tend to be more discussion-oriented. I also found that most business profs tend to put more emphasis on their lectures while math profs tend to put more emphasis on their research (in my opinion, some researchers should not be let near a classroom). I’ve had Laurier profs apply the Socratic method very effectively and I’ve had Waterloo profs read the textbook for every lecture. Obviously this is a gross generalization; I’ve also had Laurier profs who delivered bad lectures and also many Waterloo profs who were amazing and put tremendous amounts of effort into their lectures (such as inviting their famous academia colleagues to give talks).

I found, however, that Waterloo assignments and projects tended to be more interesting; Laurier courses tended to assign readings, presentations, and reports while Waterloo courses had many math proofs, coding questions, and large programming projects. I did not like the subjectivity of Laurier’s assignments and I felt that in many cases, the standards and metrics used for assessment, such as the application of different business frameworks, do not translate directly to the real-world.

Overall I’d say I generally enjoyed Waterloo courses more because it focused on hard marketable skills while Laurier courses tended to focus on frameworks and soft skills. I find frameworks to be wishy-washy and find that they often constrain thinking. Too many Laurier courses also tend to focus on teaching superficial content, which teaches memorization, as opposed to teaching skills, which involves critical thinking. I don’t agree with the forced memorization of content because it’s pointless in an age with easy access to the internet, and it also takes away time and energy which can be better used to learn actual skills.

# Extra-Curriculars

No university experience is complete without a well-balanced mix of clubs, societies and activities. For myself, I participated in intramurals (basketball and ultimate frisbee) and volunteered for various organizations, such as being a mentor for Double Degree Club and teaching economics to fundraise for Students Offering Support.

My main extracurriculars, however, were related to student governance. While I dabbled with student governance on the Laurier side, the bulk of my experiences was with the Waterloo student government. I was first the Vice President of Finance for the Mathematics Society, which represents the interests of thousands of students within the Math faculty; as VPF I managed the funds of the society, which totalled hundreds of thousands of dollars and sat on various committees, such as the board of the faculty coffeehouse. Being a part of a student government was an interesting experience; I got a first-hand look at how the bureaucracy of the university functions and a more indepth look at how power and politics work in a practical and non-theoretical setting.

After my stint as VPF, I became the Executive Director of the Math Endowment Fund, the $10+ million fund of the Math faculty which funds different projects and initiatives from Math students. As the Executive Director, I was in charge of the fund’s operations, which included traditional operations tasks such as processing proposals and participating in board meetings. I also managed the short-term strategic direction of the fund, such as holding office hours for students and meeting with alumni donors.

As with all things in life, you should always weigh the opportunity cost of doing things. You should participate in extracurriculars that add value to your life, be it the joy of helping the community, networking opportunities with industry professionals, or just doing something for fun. I found it to be helpful to think through the specifics of what you hope to gain by participating in the extracurriculars, be it something tangible like scholarships or having your own on-campus office, or something more abstract, like making new friends or developing a hobby you enjoy. The gain can be altruistic, such as helping raise money for a worthy cause or helping out directly with a project you’re passionate about. Having a precise understanding of what you can gain versus the time/energy commitment helps you make more informed decisions on how to best use your own very limited time and energy. It also helps you stay focused on what value you plan to add and what value you hope to gain.

# Should I Attend University?

For most people, university is the right choice. This is largely due to societal expectations, namely the high value people place on higher education. While the trend for many degrees is one of diminishing value (more on that later), having a university degree is still required for the most lucrative careers.

All university degrees (at least from accredited institutions) demonstrate a certain degree of responsibility and conscientiousness. It demonstrates that you put in at least somewhat of an effort and showed up enough to pass and graduate. You can think of a university degree like a driver’s license; you’ll need a degree to drive but having a degree does not guarantee that one is a decent driver; it merely demonstrates a base level of competency. On top of the base value of a university degree, different degrees have widely varied values to different people (also more on that later).

Outside of value signaling, there are some tangible benefits for attending university. Depending on your learning style and the quality of the institution you’re attending, university can be an excellent place to learn new knowledge and skills. You will be placed in an environment where your chief goal is to learn as much as you can. You get to learn about a broad array of topics and receive social support from your peers and from your institution. Obviously, this style of learning is not ideal for everyone. You have to remember that a university is a business that serves thousands of students. Your academic experience at a university will not be curated to your idiosyncratic needs. You may prefer to learn faster/slower and many universities still rely on standardized testing to assess your competency. For me this system is a hit or miss; I had to take many mandatory courses that were, quite frankly, a waste of time (some courses, such as Human Resources, were so unmemorable I had completely forgotten I had taken it until I was writing my post on courses I’d taken in university). I find testing to also encourage a very specific, often overly academic and overly superficial, understanding of the content.

Many of the best uses of university are dependent on your effort to seek them out. For instance, extracurriculars like clubs and societies can often be amazing learning experiences and opportunities to network with like-minded individuals. Having a large professional network right after school can be a massive boon in kick starting one’s career. Participation in said clubs and societies can be valuable but its value is oftentimes proportional to the effort you put in. This is the same with more exclusive courses and research opportunities with profs.

University is also an excellent place to fail. You'll (hopefully) be separated from your familial support system and will be allowed to explore, take risks, and ultimately fail on your own, much like how it is in the real world. The difference, of course, is that the consequences at university are much less severe than those of the real world. University thus makes for an ideal environment for taking (smart and calculated) risks and learning how to fail. University can also be an excellent commitment device that forces one to commit to learning.

Depending on your program and university, most if not all, of the knowledge you learn will not be directly transferable to the real world. Despite this, a university degree is still one of the best ways to signal competency, especially in technical fields such as engineering or accredited fields such as accounting. There are new university competitors, however, especially for the most in demand skills such as programming. Many companies such as Google are also offering their own programs and not hiring strictly based on having a university degree.

Many university programs, especially non-technical degrees, are also seeing their value diminish over time. There are now increasingly very good alternatives to a traditional university education. One such competitor are professional colleges, which often provide better employment prospects than many university degrees and provide opportunities to those who may not be attuned to the overly academic educational system. Oftentimes the trades, at least in Canada, make much more than low-level office jobs and can have excellent career progression for the entrepreneurial tradesperson. Of course, not all college degrees are equal, and I’m not an expert on the trades but I’m sure there are resources online should you decide to pursue this path.

Another viable alternative to universities are non-degree courses or coding bootcamps. Many of said courses and bootcamps are available at a fraction of the cost of a full university degree and are designed to provide skills which can be applied right away, making graduates of said programs very attractive to certain employers. It’s also important to note that currently, this path is only (somewhat) viable for people trying to enter into tech. If you are planning to go down this route, be sure to do your research on what you can gain from the program, especially the tradeoffs compared to a full university degree. The vast majority of employers, especially those from larger companies, will prioritize university graduates over alternative educational paths, so if you want to be competitive with university grads, you’ll have to excel in other ways, such as having plenty of work experience or completing impressive side projects. Not all courses are created equal, avoid peer-submitted courses from sites like Udemy and try to complete courses that offer accreditation, such as from reputable universities or industry-recognized providers like deeplearning.ai. Coding bootcamps are a larger commitment and warrant proper research. Try to attend bootcamps that are established and well-known in the industry, many better bootcamps will have direct pipelines for employers and will even allow you to study for free in exchange for a percentage of your starting salary, should you land a job after.

There is a very select group of people for whom a university degree, or any post-secondary education, won’t really add enough value to justify pursuing. These are people who are already excelling in their selected field, be it an athlete with a very high probability of making it to the big leagues, a content creator with a large following, or an entrepreneur with a business generating substantial profits. If you’ve attained success early in life, consider yourself fortunate and consider the opportunity cost of obtaining post-secondary education. For most in this very exclusive group, further formal education will likely distract them from their true calling. If you’re unsure about whether you fall in this group, you can always still go to university and drop out if you find that university isn’t for you; many of my most successful friends are dropouts who discovered that university was not worth their opportunity costs.

Of course, there are additional considerations outside of personal growth and opportunity cost. University, at least in Canada and the US, can be expensive for people from a lower socioeconomic background or international students. If you’re in one of these situations where your safety net is not as wide or strong as the average person, university will still be worth it, but you’ll have to consider taking less risks and making sacrifices, such as pursuing a program that has more secure employment after completion and pursuing part-time work during school.

Tl;dr you should get post-secondary education unless you are extremely successful already and have a viable future doing what you’re currently doing.

Edit (Dec 23, 2023): The current atmosphere of colleges and trade schools in Canada is not good. Due to the relatively easy barrier for educational immigration to Canada, many colleges have turned into diploma mills. Some formerly reputable colleges, such as Conestoga College, are also affected by this. If you’re not an international student, I’d recommend doing research on the reputations of the colleges and picking ones that haven’t completely given up on their educational mission. If you’re considering college degrees which can also be taken in university (such as accounting or IT), I’d recommend putting in a bit more work and saving up some money for university instead.

# Should I Attend Post-Grad?

After graduating, I flirted with the idea of continuing education and getting a PhD. After looking into programs at various universities, I decided to not pursue further formal education. There were three main factors which contributed to my decision. The first was that, for me, the vast majority of my useful skills were acquired through extracurriculars, namely through working at co-op jobs and taking courses outside of university. The second was that I was also growing tired of formalized education and the kafkaesque bureaucracy behind it which limited my learning and growth. Thirdly, and most importantly, I had not prepared adequately in advance for grad school, and would’ve likely had to complete a master’s degree before I can be accepted into a top PhD program under an established supervisor.

Many professional professions, such as doctors and lawyers, will require formalized post-grad education for the accreditation. Other professions, such as accounting, can often benefit from shorter post-grad programs such as a Master’s of Accounting or an accounting diploma, in order to speed up the CPA accreditation. There are also certain master’s degrees, such as MBAs, which have ancillary benefits, namely for networking with industry peers and alums. Other than these, a graduate degree is really only necessary if you want to have a specific research role, or be involved in academia yourself. Many pure research jobs will require an advanced degree due to the lack of roles available and the large number of applicants with at least an undergraduate degree. This is especially true for the sciences, where completing a postgraduate degree is generally expected. If you want to teach or do research at a university, you’ll definitely want a postgraduate degree.

As with undergraduate degrees, not all postgraduate degrees are created equal. For master’s, you’ll want to avoid purely course-based masters. Research-based master’s is generally more valuable than a purely course-based, as it’s oftentimes more difficult to both enter and finish the program. For most people though, a master’s is often supplementary to their undergrad degree; people take a master’s to make up for what they lacked in their undergrad education, or to switch to a new career field. If one has a career field in mind (that does not require a PhD) and plans well ahead, it’s entirely possible to skip master’s and just enter the world of work right after undergrad. If you are committed to a master’s, it’s good to start preparing early, which mainly consists of just getting good grades on relevant courses.

For PhDs, the school and the supervisor matter a great deal. Unlike undergrad and master’s, where the school does not matter as much as the program, the school matters a great deal for PhDs. The prestige and the reputation of the school affects the value of the PhD, and certain universities will have a reputation for a certain field of research. The supervisor for one’s PhD also matters a great deal. Certain supervisors will have specific research interests and being in a specific research group will determine one’s research focus, funding, and support. It’s important to network with plenty of supervisors to get a better understanding of expectations and pick the one that suits you the best. Furthermore, PhDs are more political than an undergrad or even a master’s, so I would also recommend connecting to other people under your desired supervisor before committing. As with master’s, good grades are crucial, but so are academic and industry extracurriculars, such as research or TA internships. Networking with potential supervisors is a must too.

Education, as with all investments, has diminishing returns for both money as well as time and energy. There is a thing as being “too educated” and it may even hurt one’s career prospects with certain organizations if one is deemed too “academic”. I personally wouldn’t pursue a postgraduate degree unless the career that you pick requires it. There are plenty of more efficient opportunities for learning both at work and in one’s spare time.

# What Should I Study?

I mentioned previously that different degrees have different values in the workplace and in society. There are many factors to consider but the three most important ones (in my opinion) are what you’re interested in, what you’re good at, and how wealthy your family is.

You shouldn’t study something you’re not interested in, period. To be fair, unless you went to a highly specialized high school, you probably don’t know whether you’d be interested in many of the subjects in university. For instance, I’ve never written a single line of code before university so I couldn’t have known whether I like computer science or not. It is thus important to actually try to survey the courses and check out some of the content of the different post-secondary programs. Being in high school, you’ll most likely have a general idea of which subjects interest you and which subjects bore you; I’d recommend that you keep an open mind because those biases may likely just be caused by the differing quality of teachers. I’d start by deciding what broad genre of education you’re looking for and the general categories available in each type of education. I’d then keep narrowing down the different categories until I have a list of programs which interest me. It’s also important to consider that school is not the final goal, so what you’d be interested in pursuing post graduation should outweigh what you’re interested in studying.

I’d then assess my own aptitudes and how well they match against what I’m interested in. I’d also be realistic about my assessments; high school grades can be a good starting point but I’d also include more subjective metrics like how easy and fast you can consume and learn content from the different subjects. Generally, what you’re interested in and what you’re good at will align because we tend to enjoy what we’re good at, but there will be many subjects you’re interested in but don’t have any exposure or experience with. When that occurs you’ll have to make another assessment whether you’re willing to commit the effort to learn it and also whether you’d still be interested in the subject if you’re pressured to study it. Finally, if what you’re good at is not aligned with what you’re interested in, you should consider the tradeoffs of both. Many times it’s easier to switch programs within universities, but only from a program with a tougher admissions process to one that is easier, so if you’re unsure of what you want to do, it may be wise to err on the program with tougher admissions requirements.

The third point is related to how much you actually need a degree. If you come from a wealthy family with ample connections or even wealthy enough such that you don’t have to work, congratulations on being born lucky, you may attend any program that you like. If you come from a normal family with realistic financial constraints, you’ll have to consider the employability and actual perceived value of your degree.

I will address the elephant in the room; unless you have a tangible and realistic plan for how to use an liberal arts degree (such as applying for law school or teacher’s college, or pursuing relevant careers such as graphical design), I would stay away. The reasoning is thricefold. For one, arts degrees tend to have a relatively low bar for entry. This ensures that arts programs don’t receive as much competency signaling as STEM degrees because arts degrees are perceived as easier to obtain and thus less valuable. Liberal arts education also focuses on non-tangible soft skills as opposed to concrete marketable hard skills. This ensures that arts grads don’t have many employable opportunities post graduation and arts graduates almost always have to do a post-grad, and even that may not be enough to guarantee employability. The third reason is that liberal arts, in particular social sciences, used to be valuable due to the programs teaching important non-tangible skills such as critical thinking and creative problem solving. Unfortunately in recent times, many of the arts programs have been captured by (usually very “progressive”) ideologues. Traditional liberal arts skills such as how to debate and analyze conflicting ideas are no longer the focus of the programs. Instead, the programs seek to push a very specific set of political ideas and students are often bullied and coerced into not questioning said ideas. Even supporters of the ideologies being pushed must recognize that not only is this indoctrination antithetical to the whole premise of liberal arts, it also hempers the core learnings a student can receive by taking a liberal arts degree. This is a shame because even if you’re taking a STEM degree, some liberal arts courses are quite complimentary. I’ve personally been forced to take an arts course (for public speaking) and due to the subjective nature of the course, I spent more time reading and writing about miscellaneous academic articles on “progressive” social issues than actually giving speeches. My peers in the other class, however, had a fun experience doing different speech exercises. This shows that you can definitely still have a very productive and positive experience taking liberal arts programs, pending the professors and the institution, but the odds are definitely stacked against you.

That being said, not all STEM programs are equal. Degrees with higher bars of entry tend to be perceived as more valuable than degrees that are more accessible to everyone. Some degrees, such as engineering, are often perceived as more valuable because they teach more tangible skills, than, say, pure sciences degrees. This is not to say that pure sciences are not valuable (we definitely need more scientists in the world), but people who enter pure sciences should prepare to take a post-grad degree in order to compete for a relatively small pool of jobs. Even engineering degrees are not equal; some streams of engineering, such as ECE or software engineering are much in demand right now due to the dominance of the tech industry, while other streams which tend to be more specific, such as chemical engineering, tend to almost be like pure sciences degrees in terms of employment. Speaking of tech, it’s no secret that tech is one of the largest employers (with the highest salaries) at the moment. You don’t have to be a programmer to work in tech; there are many opportunities worth considering for tech-adjacent roles, such as product managers, so if your end goal is to work in tech, you may not need to be fully technical, just knowledgeable about tech. Overall though, I’d say STEM is a safer bet than arts, because it’s easier to transition from a STEM program to another STEM program and from a STEM program to an arts program, than an arts program to a STEM program.

I also want to highlight business degrees because I am also a business grad. I personally view business as closer to liberal arts than STEM. There is a wide variance on both the types of business degrees and the variety of courses on offer. I’d personally take more courses which are technical, such as finance, as those courses tend to offer more marketable hard skills. I’d also branch out and take some STEM courses as well, in particular some basic programming courses as it’s a much sought after skill even for business professionals. If all else equal, I’d choose business degrees based on the reputation of the school (more on that later). Much of the benefits of a business degree is the networking opportunities with both your peers and your alums, and more reputable programs tend to have a higher quality pool of both.

So, to summarize: you should pick something you’re interested in, that you feel confident that you can manage, and something practical (if you’re not rich). These advice are often conflicting and each come with caveats and tradeoffs. In the end, doing your own research on the subjects, understanding that school is just one step in a larger plan, is the way to minimize the risk of choosing the wrong program. If you do find yourself in a program you feel that no longer has any value to you, I find that it’s often better to pivot (even starting from scratch if you must) than buying into sunk cost and continuing to pursue your current course. Some of my most successful friends are those who have made a conscious decision to pivot into something they are truly passionate about.

I would highly recommend taking a program that includes a co-operative education component. I speak more about it in my blog post about co-ops.

# Which University Should I Attend?

Another important consideration is the university you’re choosing to attend. I’m not too familiar with universities outside of Canada, so the discussion will be centered on Canadian universities. There are many factors to consider, such as the locations of the universities and the culture at the schools. Personally, if you financially can afford it, I’d choose a school away from home. Living outside of home is an important step in becoming a functional adult, and university is an excellent opportunity to experience freedom for the first time. Most Canadian universities are located in urban centers, but there are still large differences. For instance, schools located in larger cities such as Toronto or Vancouver can have many off-campus amenities and activities while schools in smaller university towns such as Kingston or Waterloo are often more close knit as a community. Financially, it’s much cheaper to live in a smaller city. Other social considerations include what type of school culture you prefer. If you’re more into parties, smaller city schools such as Western or Laurier tend to have a more festive environment. On the other hand, more STEM or research-focused universities such as Waterloo or U of T tend to have a more academic environment.

Along with the actual atmosphere of the universities themselves, the most important consideration is what you’re looking to study. If you’re planning to study arts, please read the previous passages. If you understand the choice you’re making and wish to study the humanities, I would recommend a larger university such as U of T, UBC, or McGill. Arts do not tend to be the focus of investment for many schools, so larger, better funded schools will have better programs than relatively smaller schools, who tend to use money on programs that bring in the most money, which is usually STEM. If you’re planning to study non-humanities art, such as graphic design, the larger universities also tend to have better programs for those subjects as well, but more focused institutions, such as OCAD or even some college programs, might potentially be more suitable.

If you’re going for a STEM degree, different universities will have different fields which they’re well-known for. If you’re looking to study engineering or computer science to enter the tech industry afterwards, Waterloo is definitely the way to go (only a little biased). The co-op program is the best in Canada (and one of the best globally); you’ll have around two years of work experience when graduating, which will put you miles ahead of your peers. If you’re looking to do more engineering or computer science research or academia, then U of T is probably the best option. There is an internship option at U of T as well, but the curriculum is much more focused on theory; U of T also has a rich research pedigree, being the home institution for famous researchers such as Geoffrey Hinton. One thing to note about U of T is that while it’s relatively easy to get accepted by the programs (compared to schools like Waterloo), finishing the program can be a different story (U of T tends to weed out students in the first year). UBC, McGill, and Alberta also have solid engineering and computer science programs, and I would consider them to be on par with Waterloo and U of T. After these five, there are some smaller programs which also have decent programs, such as Queen's, McMaster, and Calgary. These programs aren’t as renowned, but can offer other benefits; for instance, my friends who completed engineering at Queen’s spoke very highly of their tight knit culture. I would do research on the specific program you’re interested in and see which institution offers the best version of said program. For pure sciences, I’d say U of T reigns supreme, followed by UBC, McGill, and Alberta. Again, specific programs will have different rankings; for instance, if you’re looking to get into med school, you may want to take health sciences at McMaster to get a higher graduating GPA to help with med school apps.

For business schools, Queen’s and Western Ivey (not the non-Ivey programs) are probably the top two for undergrad. Both schools will give you ample networking opportunities and alumni connections, particularly in competitive fields such as finance and consulting. UBC Sauder, Toronto Rotman, and McGill Desautels also have reputable programs, and the bar for entry for these three schools are also much lower than Queen’s and Western Ivey for undergrad. Some schools, such as Rotman, have a mediocre undergrad but a very strong MBA, so when doing research, be sure to specify which level of education you’re looking to attend. If you believe that you can be at the top of your program, it can be worthwhile to take a risk and attend a smaller program, such as Lazaridis at Laurier. Having graduated from Laurier and been deemed one of the top students, I received abundant support and attention from the program, such as having many one-on-one meetings with professors, exclusive networking opportunities with alumni, and opportunities to take unique courses. The school had even hired a writing consultant to look over my writing style. The opportunities afforded to me were much more extensive than what my peers received at many of the larger, more prestigious programs.

In conclusion, what school you attend is based both on personal preference and what you’d like to study. There are often tradeoffs between different schools, so doing research and speaking with some of your older peers who are attending the different schools can be helpful.

# Final Takeaways

If you’ve made it this far, I hope you’ve gleaned some insight about post-secondary education in Canada. Here are my last three takeaways on the topic.

As much as we wish we have infinite resources, our time, energy, and attention (and money) are limited. It’s important to understand that if you work hard, you can have it all eventually, but there are tradeoffs and sacrifices you’ll have to make along the way. Understanding said tradeoffs and sacrifices are crucial for making good decisions, especially in the realms of education. Likewise, understanding that education is just a means to an end (unless you plan on working in education) will help you make more rational decisions. You should think about your future career prospects; you can envision yourself working in the fields that you're interested in and even reach out to professionals already working in those fields for advice. You should also keep your mind open and be agnostic about the end destination; good education will help you discover what you are passionate about and it might not be the same thing as when you started your journey.

While I buy into the importance of being able to be present in the moment from Eastern philosophies, it’s crucial for you to be prepared for education. You shouldn’t pursue things because of outside pressures, either from society or from your parents. You should make well-informed decisions based on what your own objectives are. Don’t go blindly through life; be conscientious about your actions and take control (as much as possible, anyways) of your own destiny. If things don’t go your way (and they probably won’t at first), don’t blame your circumstances; take charge and steer your own life.

As the chef musician Action Bronson once rapped: “opportunity be knockin’”. There are so many opportunities both within and outside of school which can help you in a variety of different ways. Before attending university, I’d recommend you apply for as many scholarships as possible; any extra money goes a long way in school and most scholarships are not taxable. I’d also try any extracurriculars that interest me during first and second years. Extracurriculars are excellent ways to develop skills and meet new people. Your network will be one of your most important assets and school is an excellent place to build one. There are many networking events but I found it more helpful to meet people in professional settings, such as conferences and employer events. These events are usually free (even the conferences which can usually be reimbursed by your school), and even if you don’t end up learning anything or meet anyone interesting, you can at least bum some free food. As previously mentioned, for an adult, university is probably one of the places where the stakes for failing are the lowest. Don’t be scared to take risks, such as taking difficult courses or competing in different competitions. I found that tackling challenges just outside of my competency range helps me develop the fastest.

Post-secondary education is an exciting, nerve-racking, but ultimately very rewarding transition period. I wish you the best of luck and hope you enjoy both the ups and the downs.